Dwarves

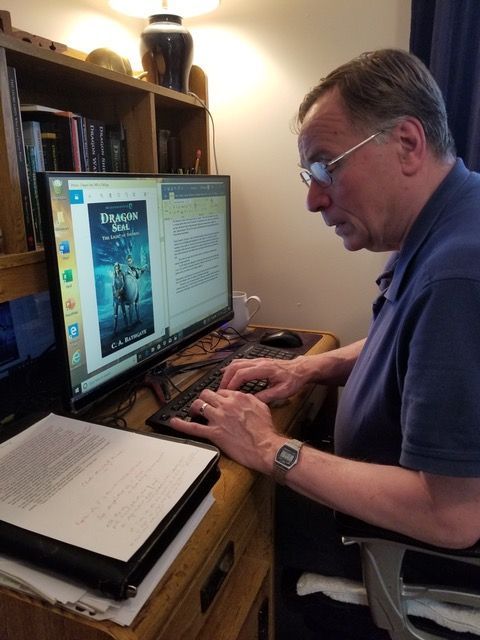

(Accompanying photo 1000_F_1296630523_dBa86kXYRBZfV1w6ZvO8uSKkI0J1y39P from stock_adobe.com) Used without commercial intent.

In a generic sense, dwarves in the world of Valdain are much as might be expected by any reader of fantasy. Stubborn, argumentative, quick to judge and act, and suspicious of outsiders. It’s also true that they are generous to a fault with friends, tenacious, and highly skilled with metal working, excavations, and brewing potent ale. This will be familiar to anyone with a literary foundation in European myths and legends, or the works of J. R. R. Tolkien.

The fractious nature of the dwarven people is illustrated in my writing. The dwarves established large, aloof communities wherever they found good rock and an abundant source of rich metals and gems. They stay clustered in single locations and build massive underground cities. These places are usually in mountainous terrain where rock is more readily accessible.

Unlike the other blessed races, dwarves don’t establish land gobbling kingdoms like humans with cycles of expansion and contraction. They don’t retreat like the xenophobic elves to shelter behind impervious arcane barriers. They don’t cower and scatter like gnomes.

In the world of Valdain, the dwarves were forced to flee from their original burrows in the west. (That’s another story.) The original refugees quarreled and split into smaller groups. Most of these bands perished, but some survived to find new mountains replete with good stone and generous veins of metal.

Eventually, eight kingdoms were founded throughout the northern continent. Mafrolmonom is Dairug’s home community north of the human kingdom of Chiardim. Astshavboke is north of Valdain, and will become prominent in later novels. Kiberbilshud is in the mountains east of Valdain. The remaining kingdoms are Nansogion, Ranuhimoir, Gendedukol, Thikuzahar and Horasterond.

Each of the dwarven kingdoms has adopted specific and unique defenses against outsiders, including attacks from avaricious dragons. The following is a brief description of three kingdoms important in the Dragonshadowed novels. A full description of each would require separate blogs.

Mafrolmonom: The youngest of the established kingdoms relies upon natural magic to form the bulwark of it’s organization and defense. The main entrance is carved from a massive lode of elemental crystal and augmented by more enchanted gems. No shadows are possible within the light of this area, while the true nature of any creature is revealed. The crystal also repels magic of all descriptions, and cancels the magical nature and abilities of intruding folk. The top of this mountain is a plateau with naturally occurring gate to the elemental air realm.

Astshavboke: Protected by the outer trade fortress of Oszuntor, the central city is divided into two distinct parts. Outside of the mountain, a trade district has been designated in which escorted non-dwarves are permitted entry. The interior city district is accessible only be true dwarves. Dwarves not native to Astshavboke must be escorted or vouched for by a local official. The underground interior is constructed in a series of circular layers, each of which has unique defenses and can be flooded with a variety of lethal materials.

Kiberbilshud: The dwarves of this kingdom have removed the surrounding mountains so that their mountain stands alone in a secluded valley surrounded by a river that divides like a moat to both sides before rejoining. Two colossal statues of dwarven warriors guard the pass, and are rumored to be juggernauts that can be activated against invasion. This kingdom relies on a number of false and trapped entrances enhanced with a variety of noxious substances including dragonbane and goblinbane.

A dwarf is recognized as an adult when they reach sixty years of age, and an exceptional individual may live up to six hundred years. Most dwarves die before their two hundredth birthday from excessive labor, war, or accident.

Every dwarf focuses on hard work, long-term planning, and attention to detail as a personal contribution to the entire community. These traits are the cornerstones of dwarvish society and culture, brought about by a need to create perfect underground living areas while almost constantly at war or preparing for war against goblins and other subterranean foes. Dwarves don’t expect help from other races during their wars, and have little time for surface conflicts. As a result, other races think of dwarves as insular and lacking empathy.

A dwarf recognizes these traits as an expression of the most valued aspects of dwarvish society: family, blood, honor and tradition. This is summed up by the four basic foundations of dwarvish creed:

- The life of a dwarf is to be respected above all else.

- Justice for all, and in all aspects of life.

- Work in the spirit of service is worship.

- Respect the privacy of another as you would your own privacy.

The underground kingdoms of the dwarves contain huge common caverns, vast market halls, and long wide passageways called ‘underways.’ Complex plumbing and air venting is engineered to keep every space comfortable. Typical underground dwarvish architecture boasts stone surfaces that are planed, smoothed, artistically shored up, and rune carved. Dwarves polish the natural beauty of stone in order to bring out the variations in texture, colour and minerals within the rock, much as wood workers utilize wood grain. The stone is further enhanced by carving and insetting gold, silver, and other reflective metals, with cleverly faceted gemstones.

Ruby, beryl and opal are popular, as these gems catch, reflect and scatter light from crystal lamps and chandeliers. Arches and flying buttresses are a common and recurring feature of all dwarven architecture. Dwarves do not consider any area truly finished until all stages of stonework are completed. Many common passages and almost all private living areas will include paintings, tapestries and banners. Aside from traditional runes which promote dwarvish virtues, decorations honor history, heroes, leaders and deities.

Surface races (called brightsiders by dwarves) are often pleasantly surprised to discover that dwarven kingdoms are well lighted, using a variety of underground lichens, fungus, bioluminescent creatures, naturally glowing stones, and smokeless oils. Dwarves are perfectly able to navigate in pitch blackness, but prefer the cheerfulness of light to enhance the colours of artwork and the natural beauty of polished stone. The only areas of a dwarvish community which are always dark are mines, to avoid triggering explosive gasses and for security purposes.

Living spaces for dwarves always reflect dwarvish culture, whether in common areas in which even non-dwarves are permitted, or private family quarters. Bright coloured banners and tapestries depicting common pastimes, legends, family feats, special occasions or great victories are displayed in public. These areas also boast of sunlight and starlight reflected through cleverly mirrored light wells for illumination of a unique carving, or into mirror pools and fountains to create a diamond-like effect. Wide, curving stairs allow viewing of carved and polished walls. Intricate and jeweled armor and weapons may also be displayed in areas reserved for important meetings or an audience with the ruler, as a means of over awing visitors with the wealth and martial capabilities of the kingdom.

Each dwarven kingdom is ruled by a king and queen, and will recognize a master smith, a master artificer, and other ‘masters’ according to need.

The community itself is composed of many ‘clans’, which are the equivalent of families or houses in a human community. Precedence of each clan is established by the wealth and date of founding. The leaders of the various clans form a conclave. The purpose of the conclave to make internal decisions and resolve disputes which are considered too minor to bring before the king. They are understood to be under the authority of the king, and meet to provide council as required. The exact composition of each conclave varies according to each kingdom, and may be as small as a few chosen members, or many hundreds of dwarves. Members of the conclave wear dark blue robes when in council or performing an official duty.

Dwarven clans are usually also famous for one or more special crafts, such as engineering, stone work, forging, or gem cutting. The established guild master’s word is law within a work area, and may over rule the direction of a chieftain or thane. Each clan has a special clan name, which is taken as the second name by every dwarf. These clan names are more important than a mere clan grouping, as the clan name allows every clan dwarf to share in both the glory and shame of the clan collective.

As males heavily outnumber dwarven females, all female dwarves are honored and protected. Females that venture into the outer world usually do so in the company of many males. They wear false beards and act as junior dwarves who rarely speak.

While most dwarves are fiercely loyal to their family, house and kingdom, an offending dwarf is punished if they succumb to greed or commit an atrocity. Execution, even for murder, is considered an honorable sentence among dwarfs.

In extreme cases suffering prior to eventual death is required. The guilty dwarf is labelled as ‘slag’ or ‘slaga.’ A slag is exiled from the community and marked with a dirty and unkept beard. Some slags shave their beards as an additional humiliation. A slag may only be reinstated by performing an exceptional feat of arms in service to their former community.

While most dwarves prefer to remain within their underground kingdom, some dwarves seek adventure, wish to travel, or are otherwise forced to leave their kingdoms as traders or ambassadors to the surface world. These are the most likely to be encountered by surface dwellers unless they run afoul of a slag.

Most crafts are worked in stone, or occasionally crystal as lesser materials tend to wear out over the life span of the average dwarf. They see no purpose to creating a masterwork which will only last a century or two. As such, their preferred material is stone, which is summed up in the common dwarf remark “stone endures.”

. . . and the dwarves endure as well.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The following is a special treat for my readers which may appear as a scene in my 10th Book. It’s a rare event in which the dwarf, Dairug, recounts an adventure from his youth. The story also provides insight into the culture and life of a dwarven band.

“It didn’t seem like much at the time . . .” Dairug paused and surveyed his companions over the light of the camp fire as he tried to read their expressions. The ruddy light cast unfamiliar shadows over their faces, and the smoke sting didn’t help clear the matter.

“Hrrrump.” He cleared his throat, aware that everyone knew he was stalling. Easy for humans to talk about their past. Not dwarves.

“I was with a survey party of five other dwarves led by Master Ordrik and his son, Orgar. He took two brothers, Broin and Burin, as guards in case of trouble, and the cleric, Granikar, for healing. He included me because he needed an engineer and I’d just made a name for myself saving a mine from the crumbler. And my share of anything we found wouldn’t cost him much.”

The dwarf glared. No one commented about his admission. They don’t want to give me an excuse to stop my story. “It was a few winters after the big battle where we joined with humans against the wizards and their gobbos. The mountains between our lands were calm and the humans were prospecting. Ordrik figured to try his luck, maybe get rich. If nothing else, humans are poor at finding good strikes, so he’d sell them locations to anything not worth his while.”

Areskel smirked. “Those were good times. Good hunting.”

“Hunting?” queried Tamsin. “I thought you didn’t eat meat.”

“Gobbos,” replied the elf. “Apologies for the interruption.” He waved his hand for the dwarf to resume his tale.

Dairug ‘hrruphed’ again. “We followed a likely dry creek bed up a ravine where the rock was exposed. It was night, so the stone and any surface metal would cool differently making anything worthwhile easier to see. That’s the advantage of keen dwarvish infravision.” He glanced at Rarnok, but the hurk kept silent.

“We didn’t find anything worth marking when Burin called a halt. Someone, humans likely, had made a dry pond across the ravine. They’d built up a scree behind a stone wall to catch water or reduce the impact of a flash flood. Whichever. There were some twigs caught at the base, and an easy sloping path to the right so animals might drink, but no water.

“The choice was to continue on by descending into the dry pond or retrace our steps. Like I said, ‘it didn’t seem like much at the time.’ Master Ordrik decided to continue in hopes of better luck higher up.

“Everyone clambered down except for Broin, who was guarding the rear. He’d just tipped himself over the dam edge when the gobbos attacked. Arrows everywhere. But they’re lousy shots and all they hit was armor and shields. They were all lined up on a ledge where we couldn’t reach them. Howling like banshees because they figured we were finished.”

His friends leaned forward, intent on catching every word.

“Everyone but the fighters dashed under the gobbo’s ledge for cover. Burin ran to the shallow slope to find another way. That’s when his foot went through the dirt covering a wicker frame and we realized we were in a pit. Broin tried to follow, but he’d wrecked one of his legs and fell.”

Waving his hands, Dairug’s voice rose. “Granikar dashed to heal Broin or drag him back and took an arrow for his trouble. Burin broke free and used his shield to cover his brother and the cleric, then dragged them back to the rest of us. We patched our hurts as best as we could, but Granikar only knew simple healing. It was a tight spot with the gobbos carrying on with whoops and hollers.” The dwarf spat.

“Dwarves don’t panic. We had two good shields for protection and were under the lee of the cliff ledge so the gobbos couldn’t get a clear shot. All we had to do was sit tight and wait for the day star to rise. The gobbos wouldn’t see so good, maybe blinded, and we’d just walk out.”

His friends all nodded understanding. Even Rarnok.

“They used ropes so that one of their archers could lean out with his bow. Orgar had a crossbow and picked him off. It got real quiet. We figured we’d be all right.

“Trouble was, gobbos can be very clever when it come to traps and killing. Water started pouring down the creek bed.”

“Unpleasant, certainly, but you could still cling to the rock face,” said Tamsin.

“Maybe you humans, or an elf. You’ve heard me say, ‘dwarves don’t swim, they sink’? We’re sturdy folk. Heavier muscle mass that allows us to endure when others can’t go on. We’re like stone, can’t swim even if we knew how. Just like trolls.”

“Trolls can’t swim? I never knew that,” murmured Gyrfalcon.

“They were going to drown you,” said Tamsin.

“Aye. And nothing we could do about it. Or so it appeared.”

“So how’d you escape?” asked Rarnok, clearly impatient.

“Dwarven smarts.” Dairug tapped the side of his head. “You remember how I said the gobbos were on a ledge above us? All gathered in a tight group to watch us panic or listen to us drown. Well, we were on a mining expedition and had mattocks. I pointed to where the rock face was weak. We hammered that rock as only dwarves can. Brought the whole face down, gobbos and all while we covered up with the shields.”

Dairug grinned. “The gobbos got themselves a nice bath before we chopped those still able to fight. The others drowned while we boosted ourselves free.”

“Never underestimate a dwarf,” confirmed Areskel. “Especially around stone.”